Description

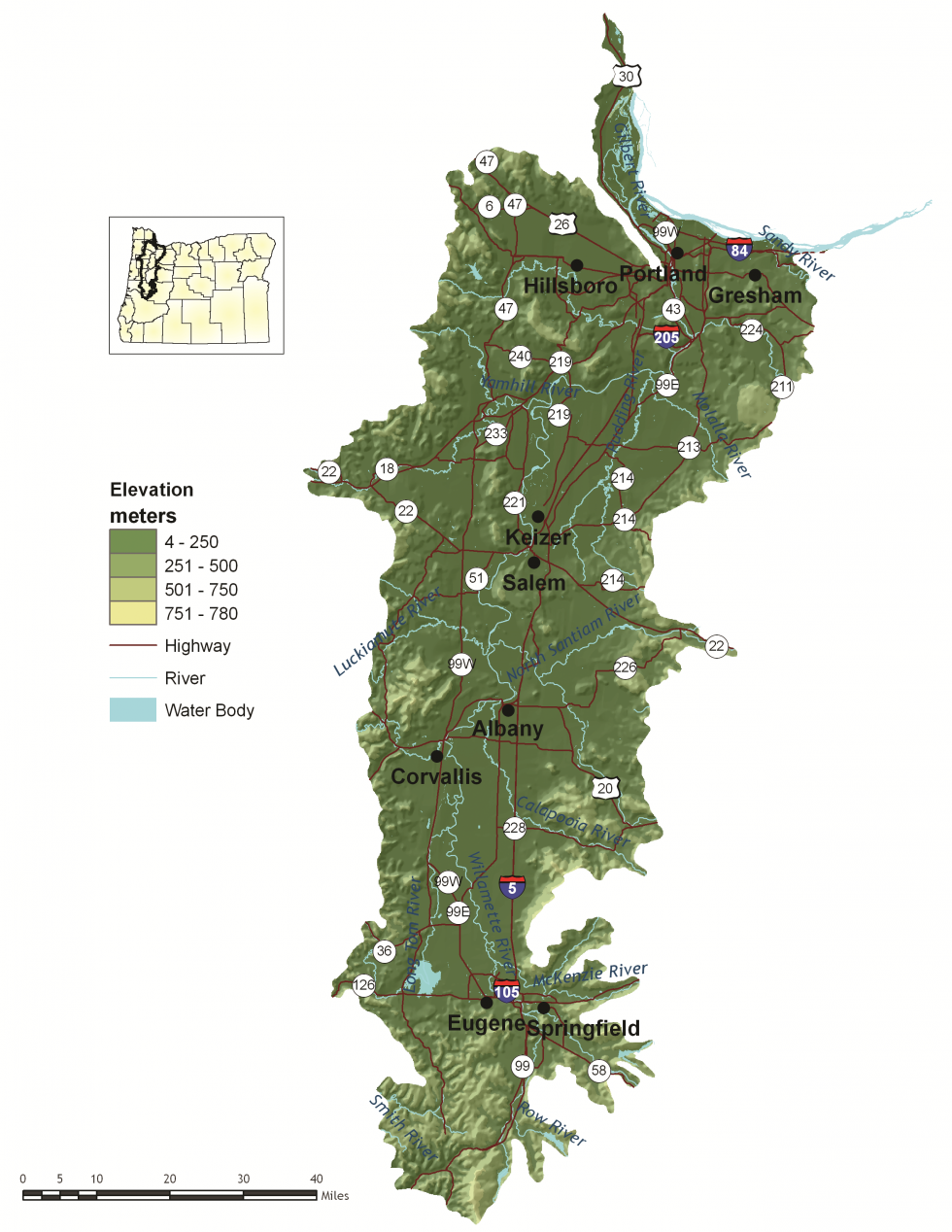

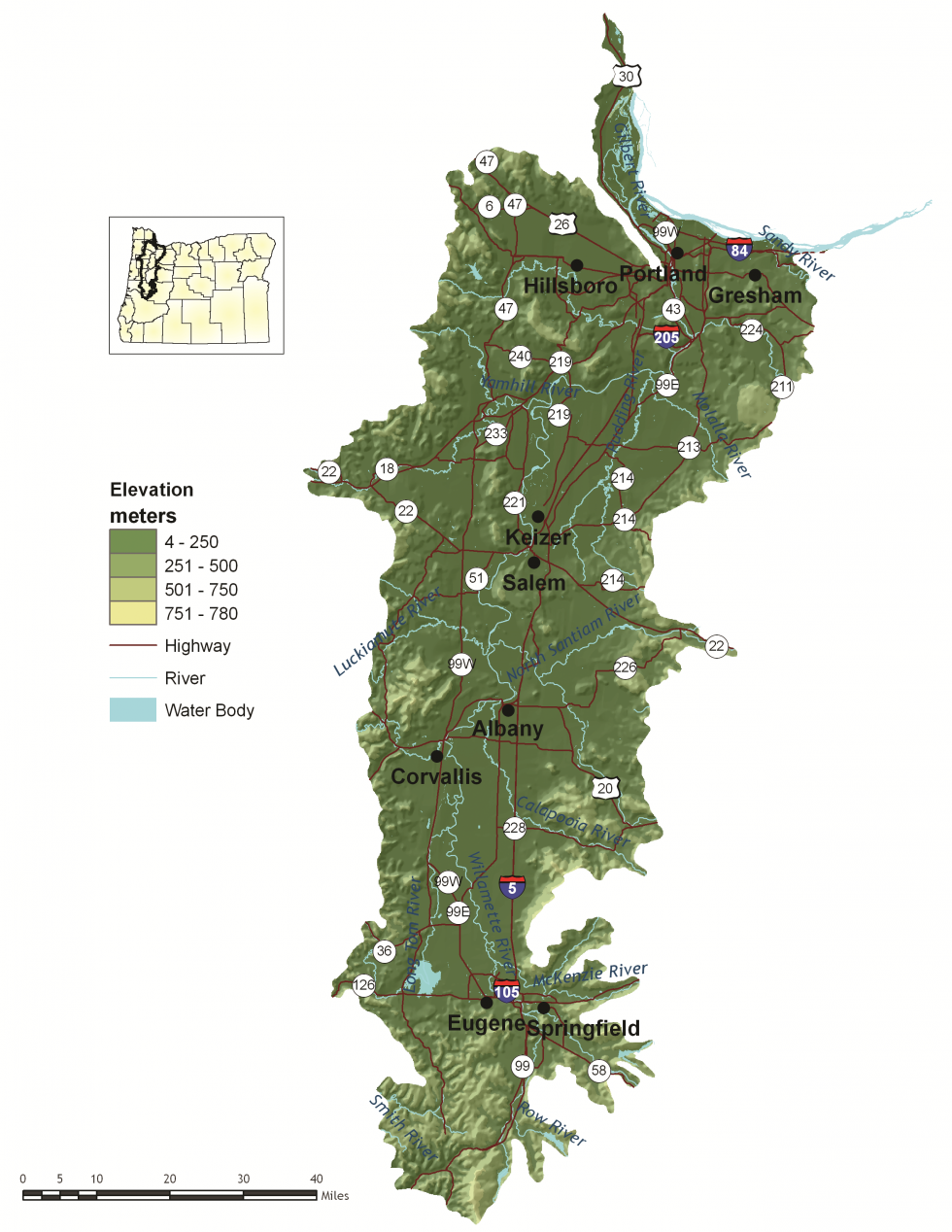

Bounded on the west by the Coast Range and on the east by the Cascade Range, this ecoregion encompasses 5,308 square miles and includes the Willamette Valley and adjacent foothills. Twenty to 40 miles wide and 120 miles long, the Willamette Valley is a long, level alluvial plain with scattered groups of low basalt hills. Elevations on the valley floor are about 400 feet at the southern end near Eugene, dropping gently to near sea-level in Portland. The climate is characterized by mild, wet winters and warm, dry summers. Fertile soil and abundant rainfall make the valley the most important agricultural region in the state.

Culturally, the Willamette Valley is a land of contrasts. Bustling urban areas are nestled within productive farmland. Traditional industries and high technology contribute to the vibrant economy. With Interstate 5 running its length, the Willamette Valley’s economy is shaped by the transportation system and the flow of goods. With 9 of the 10 largest cities in Oregon, the Willamette Valley is the most urban ecoregion in Oregon. It is also the fastest-growing ecoregion. Pressure on valley ecosystems from population growth, land use conversion, and pollution is likely to increase.

Characteristics

Important Industries

Agriculture, manufacturing, high technology, forest products, construction, retail, services, government, health care, tourism

Major Crops

Nursery and greenhouse plants, grass seed, wine grapes, Christmas trees, poultry, dairy, vegetables, small fruits and berries, nuts, grains, hops

Important Nature-based Recreational Areas

Forest Park, Bybee and Smith Lakes, Willamette River, Willamette Valley National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Fern Ridge Reservoir

Elevation

4 feet (Columbia River) to 780 feet (near Lowell)

Important Rivers

Willamette, McKenzie, Santiam, Sandy, Mollala, Clackamas, Tualatin, Yamhill, Luckiamute, Long Tom

Limiting Factors and Recommended Approaches

Limiting Factor:

Land Use Conversion and Urbanization

Habitat continues to be lost through conversion to other uses.

Recommended Approach

Landscape Scale: Because so much of the Willamette Valley ecoregion is privately-owned, voluntary cooperative approaches are the key to long-term conservation using tools such as financial incentives, Candidate Conservation Agreements with Assurances, and conservation easements. Careful land use planning is also essential. Work with agency partners to support and implement existing land use regulations to preserve farmland, open spaces, recreation areas, and natural habitats. Monitor changes in land uses across the landscape and in land use plans and policies.

Within Urban Areas: Parks and natural areas, wildlife corridors, and green infrastructure can contribute to conservation, connect people to the natural environment, and enhance the quality of life in communities.

Limiting Factor:

Altered Fire Regimes

Maintenance of open-structured Strategy Habitats, such as grasslands, oak savannas, and wet prairies, is dependent, in part, on periodic burning. Fire exclusion has allowed succession to more forested habitats. Reintroduction of fire poses significant management problems in many areas of the valley. These problems include conflicts with surrounding land use, smoke management, air quality, and safety.

Recommended Approach

Use multiple tools, including mowing and controlled grazing, to maintain open-structured habitats. Ensure that tools are site-appropriate and implemented to minimize impacts to native species. Reintroduce fire at locations where conflicts, such as smoke and safety concerns, can be minimized. Work with communities to ensure that air quality and other local concerns are addressed.

Limiting Factor:

Altered Floodplain

The floodplain dynamics of the Willamette River have been significantly altered. Multiple braided channels dispersed floodwaters, deposited fertile soil, moderated water flow and temperatures, and provided a variety of slow-water habitats, such as sloughs and oxbow lakes. The Willamette River has largely been confined to a single channel and disconnected from its floodplain.

Recommended Approach

While restoration of multiple channels may be neither practical nor desirable, cooperative efforts are needed to restore floodplain function and critical off-channel habitats. Using green infrastructure and careful planning for development outside of floodplains can help maintain floodplain function.

Limiting Factor:

Habitat Fragmentation

Habitats for at-risk native plant and animal species are largely confined to small and often isolated fragments, such as roadsides and sloughs. Habitat fragmentation also limits species’ ability to move across the landscape to fulfill life history needs. Opportunities for large-scale protection or restoration of native landscapes are limited. Barriers to large-scale ecosystem restoration include:

- existing development

- growth pressures

- high land costs

- fragmented land ownerships

Recommended Approach

Broad-scale conservation strategies will need to focus on restoring and maintaining more natural ecosystem processes and functions within a landscape that is managed primarily for other values. This may include an emphasis on more “conservation-friendly” management techniques for existing land uses and restoration of some key ecosystem components, such as river-floodplain connections and wetland and riparian habitats. “Fine-filter” conservation strategies that focus on needs of individual Strategy Species and key sites are particularly critical in this ecoregion.

Limiting Factor:

Invasive Species

Invasive plants and animals disrupt native plant and animal communities and impact populations of at-risk native species.

Recommended Approach

Emphasize prevention, risk assessment, early detection, and quick control to prevent new invasive species from becoming fully established. Use multiple site-appropriate tools (e.g., mechanical, chemical, biological) to control the most damaging non-native species. Prioritize efforts that focus on key invasive species in high priority areas, particularly where Strategy Habitats and Strategy Species occur. Work with the Oregon Invasive Species Council and other partners to educate people about invasive species issues and to prevent introductions of potentially high-impact species, such as the zebra mussel. Provide technical and financial assistance to landowners interested in controlling invasive species on their properties. Promote the use of native species for restoration and revegetation.

Limiting Factor:

Wildlife Hazards

Urban landscapes can present a variety of hazards for wildlife, such as bird collisions with windows, impacts due to light pollution, predation and disturbance by pets, collisions with vehicles and power lines, exposure to pesticides and contaminants, and harassment and illegal take of wildlife. These hazards can significantly impact wildlife and undermine habitat conservation efforts.

Recommended Approach

Support and promote innovative campaigns and programs to reduce wildlife hazards. Work with municipalizes to develop policies, such as wildlife-friendly building guidelines, wildlife-friendly lighting strategies, and integration of wildlife crossings into transportation plans to reduce hazards. Support research into better understanding of urban wildlife hazards and the management strategies to reduce those hazards. Communities can establish “Adopt a Park” programs where residents volunteer to weed a park instead of applying pesticides. Communities, local governments, and non-profit organizations can promote bird-friendly building design and outreach efforts about the impacts of cats on wildlife.

Strategy Species

Acorn Woodpecker

Melanerpes formicivorus

Bradshaw’s Desert Parsley

Lomatium bradshawii

Bull Trout, Willamette SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

California Floater Freshwater Mussel

Anodonta californiensis

California Myotis

Myotis californicus

Cascade Torrent Salamander

Rhyacotriton cascadae

Chipping Sparrow

Spizella passerina

Chum Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus keta

Clouded Salamander

Aneides ferreus

Coastal Cutthroat Trout

Oncorhynchus clarki clarki

Coho Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Columbia Torrent Salamander

Rhyacotriton kezeri

Columbian White-tailed Deer

Odocoileus virginianus leucurus

Common Nighthawk

Chordeiles minor

Dusky Canada Goose

Branta canadensis occidentalis

Eulachon

Thaleichthys pacificus

Fall Chinook Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Fender’s Blue Butterfly

Icaricia icarioides fenderi

Foothill Yellow-legged Frog

Rana boylii

Fringed Myotis

Myotis thysanodes

Golden Paintbrush

Castilleja levisecta

Grasshopper Sparrow

Ammodramus savannarum perpallidus

Great Spangled Fritillary

Speyeria cybele

Hoary Bat

Lasiurus cinereus

Howellia

Howellia aquatilis

Kincaid’s Lupine

Lupinus oreganus

Monarch Butterfly

Danaus plexippus

Nelson’s Checkermallow

Sidalcea nelsoniana

Northern Red-legged Frog

Rana aurora

Northern Spotted Owl

Strix occidentalis caurina

Northwestern Pond Turtle

Actinemys marmorata

Olive-sided Flycatcher

Contopus cooperi

Oregon Chub

Oregonichthys crameri

Oregon Slender Salamander

Batrachoseps wrighti

Oregon Vesper Sparrow

Pooecetes gramineus affinis

Pacific Lamprey

Entosphenus tridentatus

Peacock Larkspur

Delphinium pavonaceum

Purple Martin

Progne subis arboricola

Short-eared Owl

Asio flammeus flammeus

Silver-haired Bat

Lasionycteris noctivagans

Southern Torrent Salamander

Rhyacotriton variegatus

Spring Chinook Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Willamette SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Stonefly

Capnia kersti

Streaked Horned Lark

Eremophila alpestris strigata

Summer Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Taylor’s Checkerspot Butterfly

Euphydryas editha taylori

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat

Corynorhinus townsendii

Wayside Aster

Eucephalus vialis

Western Bluebird

Sialia mexicana

Western Brook Lamprey

Lampetra richardsoni

Western Bumble Bee

Bombus occidentalis

Western Gray Squirrel

Sciurus griseus

Western Meadowlark

Sturnella neglecta

Western Painted Turtle

Chrysemys picta bellii

Western Rattlesnake

Crotalus oreganus

Western Ridged Mussel

Gonidea angulata

Western River Lamprey

Lampetra ayresii

White Rock Larkspur

Delphinium leucophaeum

White Sturgeon

Acipenser transmontanus

White-breasted Nuthatch

Sitta carolinensis aculeata

White-topped Aster

Sericocarpus rigidus

Willamette Daisy

Erigeron decumbens

Willow Flycatcher

Empidonax traillii

Winged Floater Freshwater Mussel

Anodonta nuttalliana

Winter Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Winter Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Willamette SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Yellow-breasted Chat

Icteria virens auricollis

Conservation Opportunity Areas

Banks Swamp [COA ID: 062]

Also known as Killin Wetlands and Cedar Canyon Marsh, this 590-acre Metro-owned site is located west of Banks in the Tualatin River watershed.

Baskett Butte [COA ID: 072]

Located north of Dallas along Highways 22 and 99W. Upland oak-dominated hills, Basket Slough, Ash Swale, and headwaters of Salt Creek, tributary of South Yamhill River.

Bull Run-Sandy Rivers [COA ID: 105]

Area includes the headwaters of the Sandy River and its tributaries including the Bull Run River. Much of area is located within the Mt. Hood National Forest.

Calapooia River [COA ID: 082]

The Calapooia River Corridor spans from Albany through Tangent, Brownsville and through the Holley area.

Clackamas River and Tributaries [COA ID: 065]

Area extends from the Willamette River area upstream to Estacada and includes floodplain, tributaries, and upland habitats.

Coburg Ridge [COA ID: 087]

Ridgeline, foothills, and associated lowlands bordering the east side of the ecoregion from Coburg Ridge to Indian Head

Corvallis Area Forests and Balds [COA ID: 081]

This are spans the Greasy Creek and Marys River Drainages south and west of Philomath, is bordered to the west by Kings Valley, and continues through the hills west and north of of Corvallis and Adair Village through the Maxfield, Berry Creek and Soap Creek Drainages at the southerly boundary of Polk County.

Crawfordsville Oak-Washburn Butte [COA ID: 085]

Area of primarily forested, rolling hills northeast of Brownsville and the Calapooia River, southwest of Sodaville, Lebanon and Sweet Home

Deer Island [COA ID: 053]

A large (3,000+ acres) island located at River Mile 78-81 along the Lower Columbia River.

Dundee Oaks [COA ID: 066]

Area is also known as the Red Hills Conservation Area. Includes the Red Hills of Dundee, which separate the Chehalem Valley from the Yamhill River basin and headwater tributaries of the Yamhill River.

Eola Hills [COA ID: 073]

Area is located west of Salem and includes tributaries of the South Yamhill River, Willamette River, and Rickreall Creek.

Finley-Muddy Creek Area [COA ID: 084]

Located around Finley Wildlife Refuge south of Corvallis along the west side of Hwy 99; area extends up Muddy Creek west of Monroe to its confluence with Marys River

Forest Park [COA ID: 058]

This area in the Tualatin Mountains (Portland’s West Hills) includes the City of Portland’s 5,172-acre Forest Park.

Gales Creek [COA ID: 013]

The area is a late successional mixed deciduous and conifer forest with wetlands, flowing water and riparian habitats in the Gales Creek watershed. The 46 square mile area is conterminal with Nehalem and Salmonberry River Headwaters and Tillamook Bay and Tributaries COAs.

Habeck Oaks [COA ID: 074]

An area of primarily privately-owned mixed farmland and forest located north of the Little Luckiamute River along Hwy 223 between Dallas and Falls City

Hayden Island-Government Island [COA ID: 055]

Columbia River islands comprised of 826-acre West Hayden Island located north of the City of Portland just outside city limits and the Government Island complex located between River Mile 111 and 119. The complex includes Lemon and McGuire Islands and total about 2,225 acres.

Kings Valley-Woods Creek Oak Woodlands [COA ID: 080]

This corridor in Benton County extends from the south end of Woods Creek Rd. through the town of Wren, along Kings Valley Highway, to the Polk County line

Kingston Prairie-Scio Oak Pine Savanna [COA ID: 079]

The area northeast of Scio south of the North Santiam River and north of Thomas Creek

Little North Santiam River Area [COA ID: 109]

Area includes headwaters of North Santiam and Pudding Rivers, comprised largely of National Forest lands, private industrial forest and state-owned recreational areas.

Lower Sandy River [COA ID: 057]

This area is comprised of the 1,500-acre Sandy River Delta at the confluence of the Sandy and Columbia Rivers, plus the Lower Sandy River and its tributaries, including Beaver Creek and the lower reaches of the Bull Run River. Located east of the Portland Metro area in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area.

Lower Willamette River Floodplain [COA ID: 059]

The Willamette River mainstem from the confluence with the Columbia River (RM 0) upstream to Willamette Falls in Oregon City (RM26), its floodplain and adjacent uplands.

Luckiamute River and Tributaries [COA ID: 075]

The Luckiamute and Little Luckiamute Rivers and tributary drainages and associated agricultural lands surrounding the Kings Valley Area and South of Falls City.

Mary’s Peak [COA ID: 028]

Covers Mary’s Peak and surrounding wilderness area. Located north of Highway 34 and southwest of Philomath.

McKenzie River Area [COA ID: 114]

Area includes an important stretch of the McKenzie River, beginning just west of Willamette National Forest land and following the McKenzie through the city of Eugene

McTimmons Valley – Airlie Savanna [COA ID: 076]

Twelve square miles of grassland and oak savanna habitat surrounding McTimmonds Creek, north of Pedee

Middle Fork Willamette River [COA ID: 115]

Follows a significant stretch of the Middle Fork Willamette River and its surrounding riparian and upland habitat, bounded to the west by the town of Dexter and extending east to the Oakridge Airport.

Middle Willamette River Floodplain [COA ID: 060]

The mainstem Willamette River from Willamette Falls (RM 26) to the confluence with Calapooia River in Albany (RM 120), plus floodplain, and adjacent uplands.

Missouri Ridge [COA ID: 070]

Area is located between Scotts Mills and Molalla in the Rock Creek subbasin, a tributary of the Pudding River.

Mohawk River [COA ID: 088]

Relatively small (18 sq mi) COA following the Mohawk River northeast of Eugene

Molalla River [COA ID: 069]

Area comprised of Molalla River from Mulino upstream to the Dickie Prairie area, plus the lower reaches of major tributary Milk Creek.

One Horse Slough-Beaver Creek [COA ID: 083]

Area is located along the ecoregion boundary east of Albany adjacent to South Santiam River. The majority of the area is located in the One-horse slough quad

Pudding River [COA ID: 068]

Area extends from the confluence with the Molalla River upstream to the Howell Prairie area located west of Mount Angel. Includes

Red Prairie-Mill Creek-Willamina Oaks South [COA ID: 071]

Area is located south of Highway 19 along Highway 22 in the foothills of the Coast Range Mountains. Includes tributaries of South Yamhill River and associated lowland habitats.

Salem Hills-Ankeny NWR [COA ID: 077]

This area is comprised of the Ankeny National Wildlife Refuge, located south of Salem and the surrounding foothills.

Santiam Confluences [COA ID: 078]

The North Santiam River Corridor that borders Linn and Marion Counties from the confluence with the Willamette River through confluences of Jefferson ditch and Valentine Creek near Stayton and the South Santiam River ‘s Confluences with Spring Branch, Thomas Creek, Spring Creek, Crabtree Creek, Onehorse Slough, and Noble Creek to Sweet Home.

Sauvie Island-Scappoose [COA ID: 054]

This area is located north of Portland and is comprised of Sauvie Island, Multnomah Channel, the Scappoose Bay area and the eastern most slopes of Forest Park along Highway 30.

Scoggins Valley-Mount Richmond [COA ID: 063]

Area is located in the foothills of the Coast Range Mountains and includes the Upper Tualatin-Scoggins Watershed, portions of the North Yamhill River and headwater tributaries, Mount Richmond, and the Oak Ridge / Moore’s Valley area.

Siuslaw River [COA ID: 035]

This COA stretches many miles from tidally influenced to the Willamette Valley and represents may strategy habitats.

Smith-Bybee Lakes and Columbia Slough [COA ID: 056]

Smith-Bybee Lakes is located north of Portland, adjacent to the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers. The Columbia Slough flows out of Fairview Lake north of the City of Fairview, westward through a series of regulated levees to Bybee Lake. Area includes the former St. Johns landfill.

Trask Mountain [COA ID: 018]

A 37 square mile area of coast range mixed and late successional conifer forest and riparian areas of North Yamhill River wetlands. Area is conterminal with Nestucca River Watershed and Scoggins Valley-Mount Richmond COAs.

Tualatin River [COA ID: 064]

Area includes the Tualatin River and floodplain, numerous tributaries, and associated uplands from the confluence with the Willamette River upstream to Patton Valley, west of Gaston.

Upper Siuslaw [COA ID: 089]

Follows the windy Siuslaw River and surrounding habitat. Area builds from the Siuslaw Estuary COA to the west and extends east towards Cottage Grove.

Upper Willamette River Floodplain [COA ID: 061]

This area includes the Willamette River floodplain from South of Springfield in the Dexter/Lowell area north to Albany.

West Eugene Area [COA ID: 086]

This site extends from Camas Swale north along the foothills to Cox Butte, including the West Eugene wetlands

Yamhill Oaks-Willamina Oaks North [COA ID: 067]

Area is located west of McMinnville in the foothills of the Coast Range Mountains and within the South Yamhill River Watershed.