Description

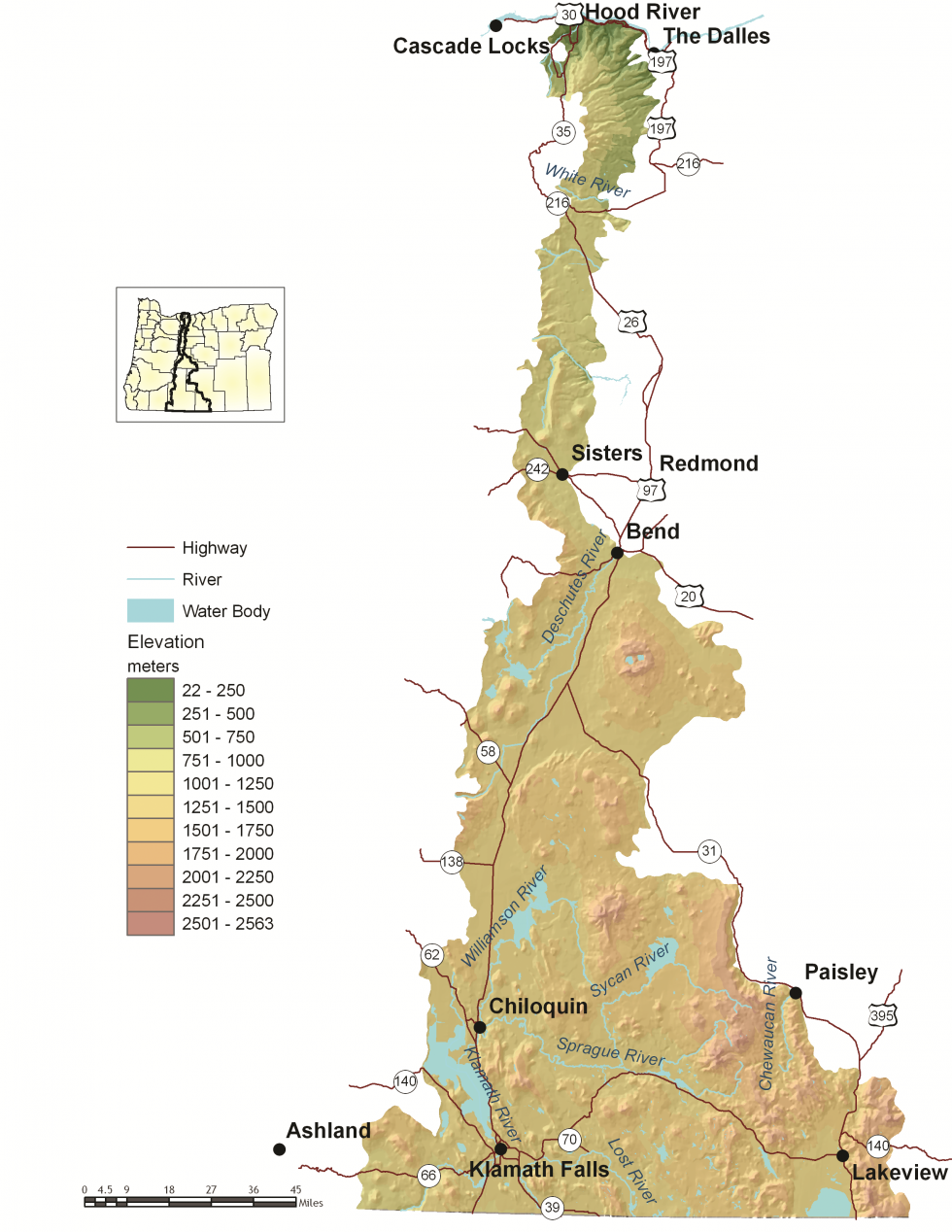

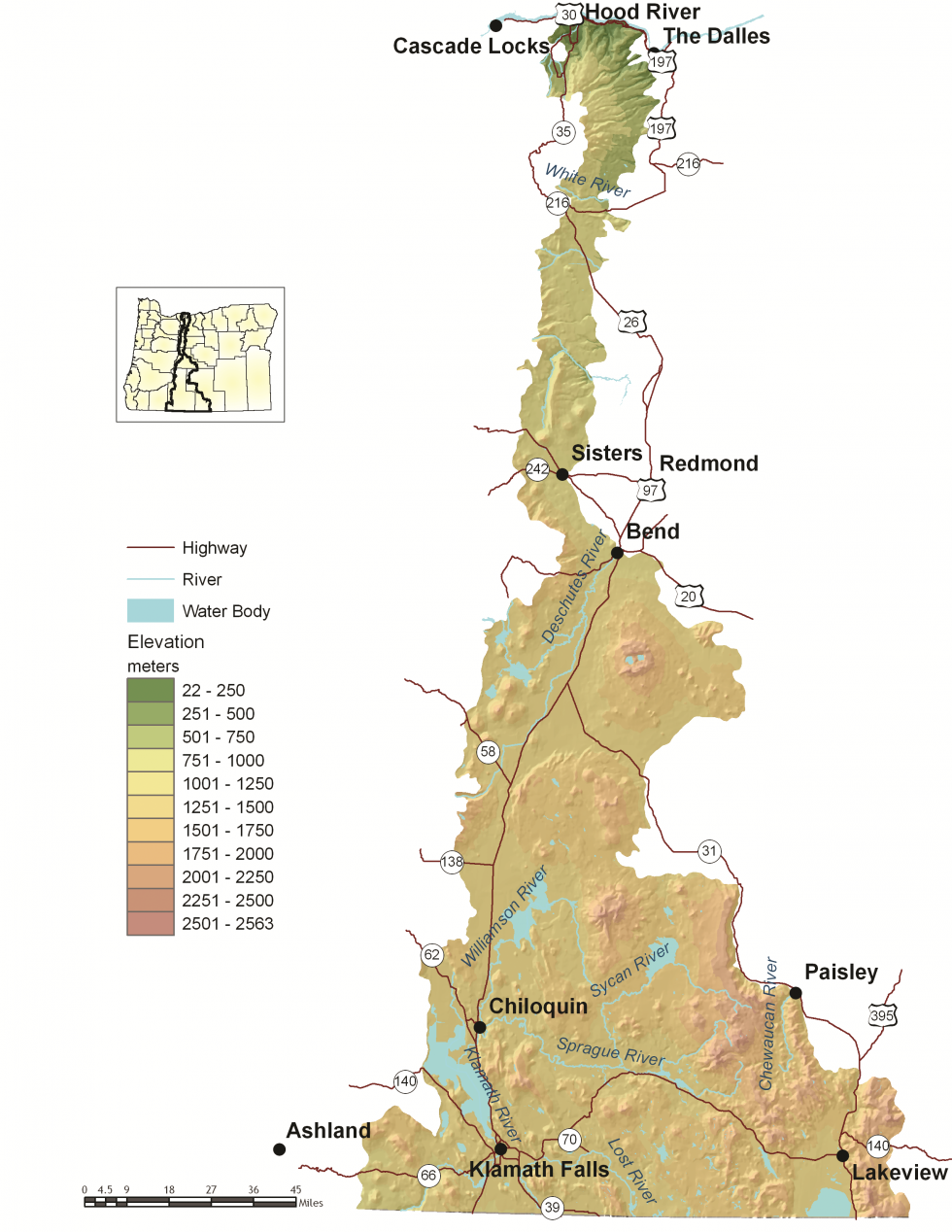

The East Cascades ecoregion extends from just east of the Cascade Mountains’ summit to the warmer, drier high desert to the east. Stretching the full north-to-south length of the state, the East Cascades is narrow at the Columbia River but becomes wider toward the California border. This ecoregion varies dramatically from its cool, moist border with the West Cascades ecoregion to its dry eastern border with the Northern Basin and Range ecoregion. The climate is generally dry, with wide variations in temperature. The East Cascades ecoregion includes several peaks and ridges in the 6,000-7,000 foot range, but overall the slopes on the east side of the Cascade Mountain Range are less steep and cut by fewer streams than the West Cascades ecoregion. The East Cascades’ volcanic history is evident through numerous buttes, lava flows, craters, and lava caves, and in the extensive deep ash deposits created by the explosion of historical Mt. Mazama during the creation of Crater Lake.

The terrain ranges from forested uplands to marshes and agricultural fields at lower elevations. The northern two-thirds of the East Cascades ecoregion is drained by the Deschutes River, ultimately flowing into the Columbia River. Most of the southern portion of the East Cascades ecoregion is drained by the Klamath River, with a small portion draining into Goose Lake, a closed basin. In general, the East Cascades is drier than the West Cascades, with fewer rivers flowing over the mountain slopes. However, the East Cascades is characterized by many lakes, reservoirs, and marshes, providing exceptional habitat for aquatic species and wildlife closely associated with water, including waterbirds, amphibians, fish, aquatic plants, and aquatic invertebrates. In fact, the East Cascades ecoregion supports some of the most remarkable biological diversity in the world.

When compared to Oregon’s other ecoregions, the East Cascades has the second-highest average income (the Willamette Valley ecoregion supports the highest per-capita income). Much of this income is related to tourism and recreation, but forestry and agriculture also provide important roles. Towns include Bend, Klamath Falls, Lakeview, and Hood River; many of these towns are experiencing rapid population growth. Most of the Warm Springs Indian Reservation is found in the East Cascades ecoregion.

Characteristics

Important Industries

Recreation (tourism and hospitality), lumber and wood, agriculture

Major Crops

Fruit (Hood River Valley), wood, potatoes, onions, barley (Klamath Basin), alfalfa, and cattle (Lake County)

Important Nature-based Recreational Areas

Klamath Marsh, Goose Lake, Newberry Crater National Monument, high Cascade lakes along Century Drive, Pine Mountain, Warner Mountains, Wilderness Areas (Gearhart, Badger Creek), Metolius and Deschutes sub-basins

Elevation

70 feet (in the Columbia River Gorge area) to over 7,700 feet (peaks in the eastern portion of the ecoregion)

Important Rivers

Deschutes, Hood, Klamath, Metolius, Link, Williamson, Sycan, and Sprague

Limiting Factors and Recommended Approaches

Limiting Factor:

Altered Fire Regimes

Past forest practices and fire suppression have resulted in young, dense mixed-species stands where open, park-like stands of ponderosa pine once dominated. These mixed conifer forests are at increased risk of forest-destroying crown fires, disease, and damage by insects. Shading from encroaching trees and fire suppression has reduced the vigor of shrubs, particularly bitterbrush, an important forage plant for mule deer. Efforts to reduce fire danger and improve forest health may help to restore habitats but require careful planning to provide sufficient habitat features that are important to wildlife (e.g., snags, downed logs, hiding cover). Similarly, wildfire reforestation efforts should be carefully planned to create stands with tree diversity, understory vegetation, and natural forest openings.

Increasing residential and resort development in forested habitats makes prescribed fire difficult in some areas and increases risk of high-cost wildfires. Although many urban-interface “fire proofing” measures can be implemented with minimal effects to wildlife habitat, some poorly-planned efforts have unintentionally and unnecessarily harmed habitat.

Recommended Approach

Use an integrated approach to forest health issues that considers historical conditions, wildlife conservation, natural fire intervals, and silvicultural techniques. Evaluate individual stands to determine site-appropriate actions, such as monitoring in healthy stands or thinning, mowing, and prescribed fire in at-risk stands. Where appropriate, thin smaller trees in the understory and develop markets for small-diameter trees.

Implement fuel reduction projects to reduce the risk of forest-destroying wildfires, considering site-specific conditions and goals. Fuel reduction strategies need to consider the habitat structures that are required by wildlife, such as snags and downed logs, and make an effort to maintain them at a level to sustain wood-dependent species. Design frequency and scale of prescribed fire to meet the habitat needs of desired focal species.

Monitor forest health initiatives and use adaptive management techniques to ensure efforts are meeting habitat restoration and forest-destroying fire prevention objectives with minimal impacts on wildlife.

Work with homeowners and resort operators to reduce vulnerability of properties to wildfires while maintaining habitat quality. Highlight successful, environmentally sensitive fuel management programs.

In the case of wildfires, maintain high snag densities and replant with native tree, shrub, grass, and forb species. Manage reforestation after wildfire to create species and structural diversity, based on local management goals.

Limiting Factor:

Land Use Conversion and Urbanization

The East Cascades ecoregion includes some of the fastest growing areas of the state (e.g., Bend, Klamath Falls, Hood River). Rapid urban and rural residential development contributes to habitat loss, and can threaten traditional land uses, such as agriculture and forestry. Urban and rural residential development can also fragment habitat into small patches, isolating wildlife populations. Increasing traffic volumes and road density associated with development creates barriers to animal movements, especially along Highway 97. Residential development is increasing in sensitive habitats, such as wetlands, riparian areas, and close to cliffs and rims where raptors nest.

Recommended Approach

Cooperative approaches with both large and small private landowners are critical. Work with community leaders and agency partners to encourage planned, efficient growth. Support existing land use regulations to preserve forestland, farmland, rangeland, open spaces, recreation areas, wildlife refuges, and natural habitats. Work with community leaders and agency partners to identify wildlife movement corridors and to fund and implement site-appropriate mitigation measures such as drift fences to overpasses or underpasses. In forested habitats, maintain vegetation to provide screening along open roads, prioritize roads for closure based on transportation needs and wildlife goals, and/or manage road use during critical periods.

Limiting Factor:

Habitat Fragmentation

In non-forested areas, habitats for at-risk native plants and some animal species are largely confined to small and often isolated fragments, such as roadsides and sloughs. Opportunities for large-scale protection or restoration of native landscapes are limited, particularly in the Klamath Basin. Existing land use and land ownership patterns present challenges to large-scale ecosystem restoration.

Recommended Approach

Broad-scale conservation strategies will need to focus on restoring and maintaining natural ecosystem processes and functions within a landscape that is increasingly managed for other values. This may include an emphasis on more “conservation-friendly” management techniques for existing land uses and restoration of some key ecosystem components such as riparian function.

Limiting Factor:

Invasive Species

Non-native plant and animal invasions disrupt native communities, diminish populations of at-risk native species, and threaten the economic productivity of resource lands.

Recommended Approach

Emphasize prevention, risk assessment, early detection, and quick control to prevent new invasive species from becoming fully established. Use multiple site-appropriate tools (e.g., mechanical, chemical and biological) to control the most damaging invasive species. Prioritize efforts to focus on key invasive species in high priority areas, particularly where Strategy Habitats and Strategy Species occur. Promote the use of native species for restoration and revegetation.

Limiting Factor:

Recreational Activity

Increasing demands for year-round recreational activity, including new mountain bike trails, ski lifts, and skill parks, can disturb wildlife. Ski seasons are becoming shorter, contributing to the demand for year-round recreational activity. New winter tire and headlamp technologies are allowing mountain bicyclists access to important wildlife areas that were previously undisturbed due to snow. Trail riding can now occur day or night, which can disturb wildlife during critical life stages. Rock climbing too close to cliff-nesting birds such as Golden Eagles can result in nest abandonment.

Recommended Approach

Plan new recreational trail systems carefully and with consideration for native wildlife and their habitats. For example, limit night riding to certain areas to minimize disturbance to wildlife, avoiding areas more sensitive to damage such as wetlands. Take advantage of abandoned or closed roads, rail lines, or previously-impacted areas for conversion into trails. Work with the land management agencies such as the USFS to designate areas as high value recreation and low habitat impact areas.

Limiting Factor:

Water Distribution in Arid Areas and Wildlife Entrapment in Water Developments

In arid areas, water availability can limit animal distribution. Water developments established for cattle, deer, and elk can significantly benefit birds, bats, and small mammals. However, some types of these facilities, particularly water developments for livestock, can have unintentional hazards. These hazards include over-hanging wires that act as trip lines for bats, steep side walls that act as entrapments under low water conditions, or unstable perches that cause animals to fall into the water. If an escape ramp is not provided, small animals cannot escape and will drown.

Recommended Approach

Continue current efforts to provide water for wildlife in arid areas. Continue current design of big game “guzzlers” that accommodate a variety species, and retrofit older models where appropriate to make them compatible with newer design standards. Use and maintain escape devices on water developments where animals can become trapped. Remove obstacles that could be hazardous to wildlife from existing developments.

Strategy Species

American Pika

Ochotona princeps

American Three-toed Woodpecker

Picoides dorsalis

American White Pelican

Pelecanus erythrorhynchos

Applegate’s Milkvetch

Astragalus applegatei

Archimedes Springsnail

Pyrgulopsis archimedis

Beller’s Ground Beetle

Agonum belleri

Black Petaltail

Tanypteryx hageni

Black-backed Woodpecker

Picoides arcticus

Bull Trout, Deschutes SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Klamath Lake SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Odell Lake SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

California Mountain Kingsnake

Lampropeltis zonata

California Myotis

Myotis californicus

Cascades Frog

Rana cascadae

Caspian Tern

Hydroprogne caspia

Coho Salmon, Klamath SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Cope’s Giant Salamander

Dicamptodon copei

Crater Lake Tightcoil

Pristiloma crateris

Dall’s Ramshorn

Vorticifex effusa dalli

Fall Chinook Salmon, Mid Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Flammulated Owl

Psiloscops flammeolus

Fringed Myotis

Myotis thysanodes

Goose Lake Sucker

Catostomus occidentalis lacusanserinus

Gray Wolf

Canis lupus

Great Basin Ramshorn

Helisoma newberryi newberryi

Great Basin Redband Trout, Goose Lake SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss newberrii/stonei

Great Basin Redband Trout, Upper Klamath Basin SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss newberrii

Great Gray Owl

Strix nebulosa

Greater Sandhill Crane

Antigone canadensis tabida

Highcap Lanx

Lanx alta

Hoary Bat

Lasiurus cinereus

Klamath Ramshorn

Vorticifex klamathensis klamathensis

Leona’s Little Blue Butterfly

Philotiella leona

Lewis’s Woodpecker

Melanerpes lewis

Lined Ramshorn

Vorticifex effusa diagonalis

Long-billed Curlew

Numenius americanus

Long-legged Myotis

Myotis volans

Lost River Sucker

Deltistes luxatus

Miller Lake Lamprey

Entosphenus minima

Modoc Sucker

Catostomus microps

Monarch Butterfly

Danaus plexippus

Northern Goshawk

Accipiter gentilis atricapillus

Northern Spotted Owl

Strix occidentalis caurina

Northwestern Pond Turtle

Actinemys marmorata

Olive-sided Flycatcher

Contopus cooperi

Oregon Semaphore Grass

Pleuropogon oregonus

Oregon Spotted Frog

Rana pretiosa

Pacific Lamprey

Entosphenus tridentatus

Pacific Marten

Martes caurina

Pallid Bat

Antrozous pallidus

Peck’s Milkvetch

Astragalus peckii

Pit Sculpin

Cottus pitensis

Pumice Grape-fern

Botrychium pumicola

Red-necked Grebe

Podiceps grisegena

Scale Lanx

Lanx klamathensis

Scalloped Juga

Juga acutifilosa

Shortnose Sucker

Chasmistes brevirostris

Sierra Nevada Red Fox

Vulpes vulpes necator

Silver-haired Bat

Lasionycteris noctivagans

Sinitsin Ramshorn

Vorticifex klamathensis sinitsini

Siskiyou Hesperian

Vespericola sierranus

Spotted Bat

Euderma maculatum

Spring Chinook Salmon, Mid Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Summer Steelhead / Columbia Basin Redband Trout, Mid Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri

Swainson’s Hawk

Buteo swainsoni

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat

Corynorhinus townsendii

Trumpeter Swan

Cygnus buccinator

Turban Pebblesnail

Fluminicola turbiniformis

Western Bumble Bee

Bombus occidentalis

Western Painted Turtle

Chrysemys picta bellii

Western Toad

Anaxyrus boreas

White-headed Woodpecker

Picoides albolarvatus

Yellow Rail

Coturnicops noveboracensis noveboracensis

Conservation Opportunity Areas

Big Marsh Creek [COA ID: 133]

Area includes river headwaters near Crescent Lake Junction and flows into Oregon Cascades National Recreation Area.

Central Cascades Crest, Southeast [COA ID: 116]

Directly adjacent to the Upper Deschutes River COA.

Chewaucan River [COA ID: 141]

Area includes the Chewaucan River and surrounding habitats

Crater Lake [COA ID: 121]

Crater Lake, Crater Lake National Park and surrounding wetlands and forest habitats.

Dry Valley [COA ID: 144]

Area includes important stretches of Dry Creek, Drews Creek and Dog Lake

Gearhart Mountain-North Fork Sprague [COA ID: 140]

Includes the North Fork Sprague river and its surrounding habitat; includes the area surrounding Gearhart Wilderness Area

Hood River [COA ID: 106]

Area includes Hood River mainstem, East and Middle Fork and numerous tributaries from confluence with Columbia River upstream. and

Klamath Marsh-Williamson River [COA ID: 134]

Large natural marsh with adjacent Ponderosa Pine forest habitat. Williamson River area spans Klamath Marsh National Wildlife Refuge and Sycan Marsh.

Klamath River Canyon [COA ID: 142]

Area follows the Klamath River to the California border

Little Deschutes River [COA ID: 132]

Area includes the Little Deschutes River, a tributary of the Deschutes River. The Little Deschutes drains a rural area on the eastside of the Cascade Range.

Long Creek-Coyote Creek-Silver Creek [COA ID: 135]

Area comprised of three major sub-watersheds immediately adjacent to Sycan Marsh, including river confluence.

Lost River Area [COA ID: 143]

Includes the Lost River Basin and surrounding native habitats

Metolius Bench-Mutton Mountains Wildlife Movement Corridor [COA ID: 150]

This long narrow COA spans two ecoregions. Within the East Cascades, it begins on the south side of the Metolius River, northwest of Lake Billy Chinook, and crosses over the river and into the Warm Springs Reservation. Heading north east, the COA crosses into the Blue Mountains ecoregion, across US Highway 26, and at its …

Metolius River Area [COA ID: 127]

Includes Metolius River basin, includes Green Ridge, and extends to include nearby valleys. Nationally known scenic recreation area that provides high quality habitat for fish and wildlife in Central Oregon.

Mt Hood Area [COA ID: 107]

Area is located within Mount Hood National Forest and includes the headwater streams of Hood, Clackamas, Sandy and White Rivers.

Newberry Crater [COA ID: 130]

Includes Newberry Crater and areas immediately west (accessible from Hwy 97). Nationally important geologic and recreation area. Includes Paulina Lake and East Lake.

Odell Lake-Davis Lake [COA ID: 117]

Includes Davis Lake and surrounding habitat, continuing west to Salt Creek and encompassing the Crescent Lake Airport

Pelican Butte-Sky Lakes Area [COA ID: 123]

At the ecoregion boundary adjacent to the East Cascades, and immediately adjacent to the Upper Klamath Lake COA in the East Cascades

Quartz Mountain [COA ID: 131]

Includes significant wetland and wet meadow areas. Immediately adjacent to NB COA “Brothers – North Wagontire”.

Soda Mountain Area [COA ID: 124]

This area is a transition zone at the nexus of three ecoregions and as a results has a high diversity of species in unique assemblages.

Sprague River [COA ID: 139]

Includes the Sprague River and its surrounding habitat.

Summer Lake Area [COA ID: 189]

This area is comprised of Summer Lake and the surrounding high desert wetlands subregion, including much of the Diablo Mountain Wilderness Study Area.

Sycan Marsh [COA ID: 136]

Includes the Sycan River, a tributary of the Sprague River with headwaters in the Fremont National Forest south of Summer Lake. Area includes surrounding areas east of Sycan Marsh.

Sycan River [COA ID: 137]

Area covers the Sycan River and surrounding area just east of Sycan Marsh

Thomas Creek-Goose Lake [COA ID: 145]

Area includes Goose Lake and surrounding habitat; and Thomas Creek and its surrounding riparian habitat. Thomas Creek is the largest tributary of Goose Lake

Upper Deschutes River [COA ID: 129]

Follows the Upper Deschutes River closely from the Cascade Crest.

Upper Klamath Lake Area [COA ID: 138]

Includes Upper Klamath Lake, the largest freshwater lake west of the Rocky Mountains. Area includes surrounding habitat to the north and adjacent to the Sky Lakes area

Warm Springs River [COA ID: 126]

Area includes the Warm Springs River (a tributary to the Deschutes River) and surrounding habitat. River flows eastward with headwaters in the Cascade Crest

Warner Mountains [COA ID: 146]

Area located east of Lakeview along the eastern border of the ecoregion

Wasco Oaks [COA ID: 125]

Area extends from the Columbia River up through the Mt. Hood National Forest and has served as an important emphasis for conservation and restoration efforts.