Background

A biological invasion is underway around the globe. In Oregon, non-native organisms are arriving and thriving, sometimes at the expense of native fish and wildlife, their habitats, and the state’s economy.

To define “invasive species”, the Conservation Strategy uses the definition from the Oregon Revised Statute 570.755 as meaning “nonnative organisms that cause economic or environmental harm and are capable of spreading to new areas of the state. ‘Invasive species’ does not include humans, domestic livestock, or non-harmful exotic organisms”. Many non-native species have been introduced to Oregon. While not all non-native species are invasive, some crowd out native plants and animals and become a serious problem.

Invasive Non-native Species

When an invasive species is introduced into a new environment, it leaves behind the natural enemies, such as predators, disease, or parasites, that controlled its population growth in its original home. Without this control, species can quickly expand, out-competing and overwhelming native species that may not have evolved the necessary survival strategies to fend off unfamiliar species or diseases.

Invasive non-native species can have many negative consequences throughout Oregon. Depending on the species and location, invasive plants can:

- affect food chain dynamics

- change habitat composition

- increase wildfire risk

- reduce productivity of commercial forestlands, farmlands, and rangelands

- modify soil chemistry

- accelerate soil erosion

- reduce water quality

Invasive species are the second-largest contributing factor causing native species to become at-risk of extinction in the United States. Invasive species also include disease-causing organisms, such as viruses, bacteria, prions, fungi, protozoans, and internal (roundworms, tapeworms) and external (lice, ticks) parasites that can affect the health of humans, livestock, and pets in addition to fish and wildlife. Non-native invasive species cause significant economic damage to landowners by degrading land productivity or values.

Pathways of Introduction

Every year, new non-native species are documented in Oregon, bringing with them the threat of ecological and economic damage. Many of these species are introduced unintentionally by people, escaping detection until it is too late to control their prolific expansion and devastating effects. As the pace of globalization and cross-border trade increases, so does the risk of introducing non-native species. Many new species will likely arrive as stowaways in agricultural commodities, seafood, livestock, wood products, packing materials, nursery stock imported into the state, and discharged ballast water from commercial shipping operations.

There are other ways people can unintentionally introduce or increase the spread of invasive species. Mud on the soles of hiking boots or treads of off-road vehicles can contain seeds of noxious weeds. Oregon’s rivers and lakes are vulnerable to aquatic invasive species, such as the highly invasive zebra and quagga mussels. These are invaders from the Ponto-Caspian Sea region and have spread to the Great Lakes, Midwest, and Southwest. Zebra and quagga mussels can be unintentionally spread as adults attached to boat hulls, motors, or trailers, or as larvae in livewells or standing water found in boat motors.

People have also intentionally released new species into the environment; some may become invasive and others may not. People depend on a variety of non-native plants for food, livestock feed, and ornamental, medicinal, and other uses. While most of these plants have little environmental effect, some like the Scotch broom, Japanese knotweed, and Armenian (Himalayan) blackberry can escape into natural areas. When this happens, they can crowd out native plant communities. Non-native fish (both legal introductions and illegal releases), bullfrogs, feral swine, and birds have been released to provide new fishing and hunting opportunities. Nutria, which cause tremendous damage in agricultural areas, were released in Oregon after failed attempts at raising them commercially for fur. People release pet amphibians, reptiles, and mammals into backyards, and aquarium fish into local streams and ponds. In many cases, these releases are illegal in Oregon.

Once introduced, natural pathways may help to spread invasive species, especially plants whose seeds or parts are easily dispersed by wind, water, and wildlife. Certain land management practices can serve as conduits or create conditions that favor the spread of invasive organisms. Regardless of the pathway or practice implicated in the problem, experts believe that environmental disturbance is often a precursor to invasion by non-native plants. Invasive non-native species are highly adaptable and competitive, using space, water, and sunlight of disturbed ground. Following introduction and successful establishment, these species may increase their dominance and distribution until they reach the environmental and geographic limits of their expansion. Populations of invasive species may stabilize eventually but often not before inflicting significant environmental and economic damage.

Although introductions of invasive species to Oregon may be inevitable, preventing invasive species from arriving in the first place is the most cost-effective way of controlling invasive species and is in everyone’s best interest.

Assessing Risk

Evaluating the potential danger associated with the introduction of a new species is sometimes very difficult due to unknown variables on how the species will respond in a new environment or which species might arrive within the state. Many invasive species, especially those that are aquatic (e.g, invasive tunicates) can be difficult to detect before they pose a large threat. Once invasive species are established, controlling them can be difficult, expensive, and in some cases, impossible. Priority must be placed on preventing the introduction of new species. Also, not every new non-native species is equally threatening, so gauging the level of risk and responding accordingly is important to avoid misallocating limited resources on species of low ecological or economic concern.

The Conservation Strategy uses a systematic approach to assess the level of ecological threat from invasive species currently present in Oregon or likely to appear in the near future. These priority invasive species are listed by Ecoregion. To develop these lists, the ODFW coordinated with Oregon Department of Agriculture (ODA) invasive species program staff. The scope was limited to terrestrial and aquatic vertebrates.

Beginning in 2012, an effort was initiated to assess existing or potential threats to marine and estuarine ecosystems. The ODFW developed a list of non-native species, in consultation with the OSU, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), USGS, and Williams College. This list includes fish, invertebrate, plant, and algae species within the nearshore ecoregion and is presented within the Nearshore Strategy.

Many non-native fish species are legislatively defined as game fish in Oregon and are managed by ODFW. Managed appropriately, they provide a valuable fishery to the public and an economic stimulus to many communities in Oregon. The ODFW provides angling opportunities for some of these species by transplanting fish from one waterbody to another, stocking hatchery-produced fish in locations where impacts to native fish are believed to be acceptable, or transplanting fish to ponds more accessible for angling.

In some situations, non-native fish species move around naturally after environmental or habitat disturbance events, or are moved by people either unintentionally or illegally to stock them for harvest or some other purpose. When this happens, non-native fish species can become naturally self-sustaining, potentially impacting Oregon’s native species. The ODFW seeks to prevent the uncontrolled spread of these species and will evaluate situations on a case-by-case basis. In some situations where populations have already become established and there is little feasibility of eliminating their natural production, the ODFW will manage fisheries for the public, establishing seasons and take limits. In other situations where the introduction is very recent or particularly harmful to native fish and wildlife, the ODFW will assess management options to remove them, limit further dispersal, and prevent the illegal establishment of fisheries.

Documented Non-native Invasive Fish and Wildlife Species

| Species | Blue Mountains | Coast Range | Columbia Plateau | East Cascades | Klamath Mountains | Northern Basin & Range | West Cascades | Willamette Valley | Nearshore |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) | BM | CR | CP | EC | KM | NBR | WC | WV | NS |

| Amur Goby (Rhinogobius brunneus) | CR | WV | |||||||

| Asian Clam (Corbicula fluminea) | BM | CR | CP | EC | KM | NBR | WC | WV | NS |

| Asian Marsh Snail (Assiminea parasitologica) | CR | NS | |||||||

| Asian Sea Squirt (Styela clava) | CR | NS | |||||||

| Australasian Burrowing Isopod (Sphaeroma quoianum) | CR | NS | |||||||

| Black Rat (Rattus rattus) | CR | CP | EC | WC | WV | ||||

| Brown Rat (Rattus norvegicus) | BM | CR | CP | EC | KM | NBR | WC | WV | |

| Chinese Mysterysnail (Cipangopaludina chinensis malleata) | CR | EC | KM | WV | |||||

| Colonial Tunicate (Didemnum vexillum) | CR | NS | |||||||

| Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio) | BM | CR | CP | EC | KM | NBR | WC | WV | |

| Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) | CR | KM | WC | WV | |||||

| Eastern Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger) | BM | NBR | WV | ||||||

| Eastern Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) | NBR | WV | |||||||

| Eurasian Collared Dove (Streptopelia decaocto) | BM | CR | CP | EC | KM | NBR | WC | WV | |

| European Ear Snail (Radix auricularia) | BM | EC | |||||||

| European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) | BM | CR | CP | EC | KM | NBR | WC | WV | |

| Fathead Minnow (Pimephales promelas) | CR | EC | WV | ||||||

| Feral Goat (Capra hircus) | CR | ||||||||

| Feral Horse (Equus caballus) | BM | EC | NBR | ||||||

| Feral Sheep (Ovis aries) | BM | EC | |||||||

| Feral Swine (Sus scrofa) | BM | CR | CP | EC | KM | NBR | WV | ||

| Freshwater Jellyfish (Craspedacusta sowerbyi) | KM | WV | |||||||

| Golden Shiner (Notemigonus crysoleucas) | BM | CR | EC | KM | NBR | WC | WV | ||

| Goldfish (Carassius auratus) | CR | EC | KM | WV | |||||

| Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella)* | CR | CP | EC | WV | |||||

| Griffen's Isopod (Orthione griffenis) | CR | NS | |||||||

| House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) | BM | CR | CP | EC | KM | NBR | WC | WV | |

| Japanese Eel Grass (Zostera japonica) | CR | NS | |||||||

| Japanese Oyster Drill (Ocinebrellus inornatus) | CR | NS | |||||||

| Japanese Seaweed (Sargassum muticum) | CR | NS | |||||||

| Mute Swan (Cygnus olor) | BM | EC | KM | WV | |||||

| New Zealand Mudsnail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum) | BM | CR | CP | EC | KM | NBR | WC | WV | NS |

| Nutria (Myocastor coypus) | BM | CR | CP | EC | KM | WC | WV | ||

| Purple Varnish Clam (Nuttallia obscurata) | CR | NS | |||||||

| Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans) | CR | EC | KM | WV | |||||

| Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)** | BM | CR | KM | WV | |||||

| Red Swamp Crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) | CR | EC | WV | ||||||

| Ringed Crayfish (Orconectes neglectus) | CR | EC | KM | NBR | WC | WV | |||

| Rock Pigeon (Columba livia) | BM | CR | CP | EC | KM | NBR | WC | WV | |

| Siberian Prawn (Exopalaemon modestus) | CR | CP | WV | ||||||

| Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana) | BM | CR | CP | EC | KM | WC | WV | ||

| Western Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis)*** | CR | CP | KM | NBR | WC | WV | |||

| Yellow Bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta scripta) | KM | WV |

* Grass Carp may be permitted by ODFW for vegetation management in certain approved and controlled situations. (Prohibited and Controlled Fish, Mollusks, and Crustaceans)

** There is also a native Red Fox found in the Wallowa Mountains.

*** The Western Mosquitofish is a controlled species that may be used in man-made troughs or ponds that are not connected to natural waterways, in certain situations to control mosquitoes. (Oregon Administrative Rule 635-007-0620)

Data sources for this table: ODFW Prohibited and Controlled Species List; USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species; iMap Invasives; BLM; ODA; personal communications with regional experts

MANAGEMENT APPROACHES

Building on Current Planning Efforts

Several other planning efforts are underway to protect Oregon from biological invaders. State statutes or agency administrative rules are in place to prohibit the unauthorized entry of undesirable invasive species. Together, the following plans and regulations provide a foundation for addressing invasive species and put the issue into clearer context for this Conservation Strategy:

- Oregon Invasive Species Council Action Plan

- Invasive Species Report Card

- Aquatic Invasive Species Prevention Program

- Oregon Noxious Weed Strategic Plan (ODA)

- Oregon Aquatic Nuisance Species Management Plan (Portland State University)

- Ballast Water Management Administrative Rules (DEQ)

- Wildlife Integrity Administrative Rules (ODFW)

- Oregon Dreissenid Mussel Rapid Response Plan

- Columbia River Basin Interagency Invasive Species Response Plan

Other ongoing efforts provide information that would be helpful in addressing invasive species. For example, the USFS Forest Inventory and Analysis Program uses remote sensing imagery or aerial photography to classify land into forest or non-forest. Permanently established field plots are distributed across the landscape, and 10 percent of these plots are visited each year to collect forest ecosystem data. A subset of these plots are sampled yearly to measure forest ecosystem function, condition, and health, including measurements of native and non-native plants, which can provide information about the spread of invasive species.

In April 2005, the USFS released its Final Environmental Impact Statement “Preventing and Managing Invasive Plants”. Although the record of decision has not been finalized, the proposed action amends all forest plans within the Pacific Northwest Region 6 to improve and increase consistency of invasive plant prevention, and allows the use of an expanded set of invasive plant treatment tools. The proposed action includes restoration requirements and an inventory and monitoring plan framework.

Meeting the Challenge: A Framework for Action

Invasive species can be effectively managed and their potential ecological and economic impacts mitigated if the right precautions and steps are taken. The National Invasive Species Council has identified a framework of approaches in its plan, “Meeting the Invasive Species Challenge: National Invasive Species Management Plan”. These actions, or management approaches, are not a cure-all but can give states, counties, private landowners, and public land managers a framework for prioritizing efforts to guard Strategy Species, Strategy Habitats, and working landscapes against invading organisms.

For maximum effectiveness, all approaches in this Framework for Action should be integrated and carried out in a coordinated manner. The approaches need to be implemented at different spatial scales and across all jurisdictional and ownership boundaries. For example, monitoring aids site-specific management decisions. Weed infestations on federally-managed land and on adjacent private property are more effectively controlled when federal land managers and private landowners join forces at the landscape level, across ownership boundaries. Reporting these data to a central database is also important for tracking changes in populations and distributions across the state.

| Management Approach | Objective |

|---|---|

| Education | Inform the public about the impacts and costs of invasions. |

| Prevention | Preventing new species introductions is a top priority and the most cost-effective approach to protecting native species, ecosystems, and productivity of the land from invasive species. |

| Assessment/Risk Analysis | Defining the level of concern and risk associated with new introductions through an assessment process will help to identify the worst invaders and management priorities. |

| Monitoring | The importance of surveying cannot be overestimated when looking for first-time infestations of undesirable non-native species or evaluating efforts to control existing occurrences. |

| Early detection | Early discovery of infestations of previously undocumented non-native species is critical to controlling their spread and achieving complete eradication. |

| Rapid Response | Immediate treatment of new, isolated infestations will maximize eradication success and decrease the likelihood of populations expanding beyond the initial area of introduction. |

| Containment | Preventing invasive species from ‘hitchhiking’ via vulnerable pathways will slow the advance of well-established invasive species into unaffected areas. Some invasive species are tolerable if infestations can be contained and their impacts minimized. |

| Restoration | A system-wide approach to treating invasive species should consider habitat restoration as part of the ecological healing process. Helping native species and ecosystems recover is an important step following the removal of harmful species. |

| Adaptive Management | Land managers or landowners should change course on management prescriptions if treatments are not working. Monitoring the results of control actions is an important part of this process. |

Goals and Actions

Goal 1: Prevent new introductions of species with high potential to become invasive, and reduce the scale and spread of priority invasive species infestations.

Action 1.1. Focus on preventing the introduction of new invasive non-native species through collaborative efforts.

The cost and difficulty of managing invasive non-native species increases substantially once a species has established self-sustaining populations. Once established and widespread, invasive species are virtually impossible to eliminate, and control costs can become prohibitive. Therefore, every effort should be made to prevent first-time introductions of invasive species from becoming established in Oregon. By their very nature, however, state borders are porous and vulnerable to the entry of non-native organisms. A significant challenge is developing and implementing effective prevention strategies based on the best research of where and how new and potentially invasive organisms are likely to enter Oregon. An example of preventing the introduction of invasive species is the watercraft inspection program for aquatic invasive species (AIS). Inspection stations are located at entry points on major highways along the eastern and southern borders of Oregon. Personnel at these stations inspect watercraft for AIS and if any are found, the watercraft is decontaminated on the spot.

Action 1.2. Increased public awareness, reporting, and funding.

The Oregon Invasive Species Council (Council) coordinates statewide efforts to prevent biological invasions and seeks to mitigate the ecological, economic, and human health impacts of invasive species. Informed landowners, land managers, public officials, and the public can take action to further the Council’s goals. Businesses, landowners, anglers, hunters, Oregon residents, and visitors should be reminded of the dangers posed by invasive species through targeted outreach and education. People can greatly reduce the accidental introduction or spread of these organisms into and within Oregon if they know what precautions to take. State and federal agencies can work with the Council to promote and raise public awareness of programs for which they have responsibility to reduce or eliminate the risk of introducing invasive species. For example, ODA’s Noxious Weed Program provides statewide leadership for coordination and management of state-listed noxious weeds, and ODFW’s Wildlife Integrity Program regulates the importation, possession, and transportation of non-native wildlife species. Encouraging Oregonians to report sightings of invaders is also important and can be key to the detection, control, and elimination of an invasive species. The Council’s toll-free “hotline” is one such tool (1-866-INVADER).

Elected officials, industries, and the conservation community should work together to identify public and private funding to support the efforts of the Invasive Species Council and its partners to develop effective prevention measures. This investment will help protect the economic and ecological interests of all Oregonians, as well as protect Strategy Species and Habitats from the impacts of harmful invaders.

Action 1.3. Through collaborative efforts, continue to develop early detection and rapid response plans to facilitate swift containment of new introductions.

The potential dangers of new invasions to forestlands, agricultural and range lands, natural areas, and fish and wildlife should be determined as early as possible so that farmers, ranchers, fish and wildlife managers, and conservationists can be forewarned and better prepared. Response plans could be developed in a format similar to the “Columbia River Basin Interagency Invasive Species Response Plan: Zebra Mussels and Other Dreissenid Species“. Teams composed of state, federal, and private experts would determine the likely impacts of newly discovered invasive species, predict the spread of new infestations, and decide which steps should be taken to alert the public. This approach could follow the format used by interagency wildfire coordination centers. Invasive species, like wildfires, ignore ownership boundaries and spread from property to property, underscoring the need to treat invasions wherever they occur on the landscape. Also, like wildfires, invasive infestations are best controlled when small in size.

In 2012, Governor Kitzhaber developed the Oregon Tsunami Debris Task Force to respond to marine debris coming ashore with high potential to carry invasive species. The task force, led by the Office of Emergency Management, was comprised of members from the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Oregon Health Authority, Oregon State Marine Board, Oregon State Police, Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), ODFW, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Coast Guard, tribal, state, and local government, and advocacy organizations. The task force developed the Japanese Tsunami Marine Debris Plan, with the purpose of coordinating a timely, comprehensive, effective, and well-managed response to marine debris that landed on Oregon’s shores. While the plan is similar to that discussed above, it targets the mechanism of species introduction (e.g., marine debris), rather than specific species.

Rapid response plans need to be tested, refined, and practiced before implementing control efforts on a new infestation. Conducting exercises that simulate an infestation can promote better cooperation between government agencies and private organizations, and produce a more effective and successful battle against a newly detected species.

Action 1.4. Establish a system to track the location, size, and status of infestations of priority invasive species.

A number of local, state, and federal agencies and private organizations independently gather data on invasive plants, animals, and pathogens in Oregon, but the information is decentralized and often not integrated for analysis. Oregon lacks a comprehensive, coordinated, and centralized system for gathering and maintaining data on the location of non-native species on private and public lands. Efforts to institute a reporting system are also hampered, in part, by landowner privacy and disclosure concerns. Landowners may not report invasive species on their property due to concerns that disclosure of infestations may lower property values or that they may be held responsible for treatment costs.

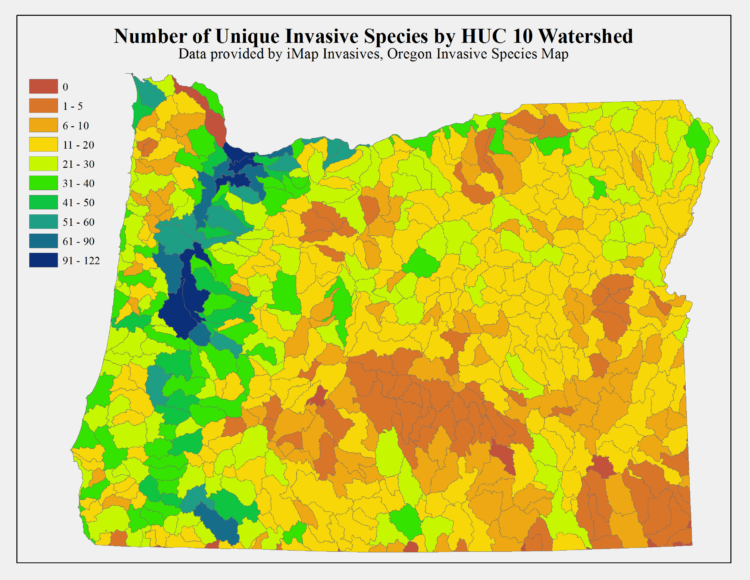

There is a critical need to improve the integration and standardization of data on invasive species derived from independent monitoring efforts. Using existing data housed by the Institute for Natural Resources at OSU, a multi-partner, spatially-explicit database and mapping system of non-native plants, animals, and diseases could be developed. The data could be used to track changes and trends in invasive populations, better anticipate the spread of invasive organisms within the state, identify vectors or points of entry and high-risk environments for invasion, and evaluate the success of management actions. Voluntary reporting by private landowners should be encouraged by providing confidentiality, nondisclosure of sensitive information, and free technical assistance on control methods to increase landowner participation.

The West Coast Governor’s Alliance has constituted a Marine Debris Action Coordination Team, with the goal of creating a framework to identify, assess, prevent, and reduce marine debris and the threats associated with debris, including invasive species. They have developed a Marine Debris Database that allows anyone to record and track information about marine debris on land or in the water, or clean-up events. While the goals of the movement are much broader than invasive species, the work that is done is critical to tracking potential invasive species threats in estuarine and marine environments.

Action 1.5. Focus on eradication of invasive species in Strategy Habitats and other high priority areas where there is a clear threat to ecosystems and a high probability of success.

Some invasive species have spread to the point where it would be impractical or impossible to eliminate them from Oregon. Yet, some of these established invasive species negatively impact Strategy Species and Strategy Habitats and can be contained at the local level. In these situations, control efforts should be focused on those invasive species that are limiting factors to Strategy Species or Strategy Habitats, particularly within Conservation Opportunity Areas. In addition, other priorities may include controlling invasive species that disrupt ecological function or impact vulnerable, commercially valuable lands, such as rangeland, farmland, and timberland.

Local eradication of invasive species near high priority habitats and lands should be emphasized where practical, with the ultimate goal of restoring these lands to their full ecological or utilitarian potential. Controlling established invasive species often requires a long-term commitment. If funding runs out or the management priorities change, invasive species can quickly return. Restoration can repair habitats degraded by invasive species and may be necessary if aquatic or terrestrial ecosystems are too damaged to heal on their own. Restoration may be the best prescription for inoculating native plant communities against invasive plants because ecosystems are more resilient to invasion when they are healthy and functioning well. Entities involved in invasive species management should encourage landowners to consider ecologically-based restoration as part of any plan to manage invasive species.

Private landowners are increasingly partnering with watershed councils, ODFW, Soil and Water Conservation Districts (SWCDs), ODA, and federal land management agencies to manage invasive species across property lines. Such broad-scale efforts need to continue and be expanded.

Action 1.6. Work with the ODA, the Oregon Invasive Species Council, and other partners to develop an invasive species implementation tool that evaluates the ecological impact and management approaches for invasive species identified as priorities in the Conservation Strategy.

The ODFW is developing an invasive species implementation tool to further evaluate invasive species. Building on already-completed assessments, this tool will rank the severity of the ecological impact of each invasive species by analyzing four factors: ecological impact, current distribution and abundance, trends in distribution and abundance, and management difficulty. This information will be used to determine the best management approaches for individual invasive species. Current and potential partners include TNC, Oregon Biodiversity Information Center, Oregon Invasive Species Council, county weed boards, federal land management agencies, ODA, and others.

Action 1.7. Develop and test additional techniques to deal with invasive species, and share information with landowners and land managers.

Landowners and land managers need to know how to treat invasive organisms that lower the productivity and value of land, alter ecosystem processes, and threaten native species. They also need to know what level of investment is appropriate, and which techniques are most appropriate for each respective situation. Throughout Oregon, people are using a variety of methods to control individual invasive species with varying degrees of success.

Multiple site-appropriate control mechanisms (e.g., mechanical, chemical, and biological) should be evaluated to control individual invasive species. Increased coordination and communication is needed between researchers, agencies, watershed councils, county weed boards, and private landowners regarding what works under what conditions. Outreach materials should be developed to assist landowners and land managers in choosing and using the most appropriate techniques for their sites. Currently, there is no known effective way to control some widespread invasive plants, such as cheatgrass, medusahead, and false brome. Research efforts need to be supported and expanded to address these and other invasive species.

Additional Resources

- Oregon Invasive Species Council

- National Invasive Species Council

- ODFW Invasive Species Resources

- ODFW Prohibited and Controlled Fish, Mollusks, and Crustaceans

- Oregon Administrative Rule 635-007-0620

- ODA Insect Pest Prevention and Management

- Global Invasive Species Database

- USFWS Invasive Species

- USGS Invasive Species Program

- USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species

- Oregon DEQ Ballast Water and Invasive Species

- BLM Oregon Invasive Species

- BLM Oregon Wild Horse Program

- 100th Meridian Initiative

- Oregon State University: Pacific Northwest Nursery Integrated Pest Management

- Oregon Sea Grant: Invasive Species